Coastal NC Environmental Justice in the News – Click Here.

Environmental Injustice

Environmental injustice has profound and far-reaching impacts on communities, especially those already marginalized and vulnerable. This issue is not just about the environment; it is inherently tied to social and economic disparities. Environmental hazards and pollutants disproportionately affect low-income communities, communities of color, and Indigenous populations, exacerbating existing inequalities.

One of the most glaring examples of environmental injustice is the uneven distribution of toxic facilities and pollutants. Many of these facilities, such as industrial plants and waste disposal sites, are strategically placed in or near disadvantaged communities, leading to health risks and adverse environmental effects. As a result, residents in these areas are more likely to be exposed to pollutants and suffer from a range of health problems, including respiratory issues, cancer, and developmental disorders.

Lead exposure, particularly through lead-based paint, is a poignant illustration of this injustice. This exposure not only affects their health but also their cognitive development, leading to long-term consequences for these individuals and their communities.

Another aspect of environmental injustice is the lack of access to clean and safe water. Many low-income communities, predominantly communities of color, face water contamination issues. Instances like the lead-contaminated water crisis in Flint, Michigan, or the lack of access to clean drinking water on Indigenous reservations, highlight the stark disparities in water quality. This not only poses immediate health risks but also perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage and undermines the basic right to clean water.

Environmental injustice also manifests in the realm of climate change. Vulnerable communities are more susceptible to the adverse effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and heatwaves. These communities often lack the resources to adapt to or mitigate the impacts of climate change, leading to displacement, loss of livelihoods, and increased health risks.

Environmental injustice affects the educational and economic prospects of communities. Children growing up in areas with high pollution levels are known to experience developmental delays and lower cognitive abilities, ultimately limiting their educational opportunities and future earning potential. This cycle of environmental injustice perpetuates poverty and inequality.

Environmental injustice is a pervasive and deeply rooted issue that goes beyond environmental concerns. It is a matter of social and racial equity, health disparities, and economic opportunities. Addressing this problem requires not only environmental policies but also a broader commitment to social justice and the recognition that all communities deserve access to a clean and safe environment.

Environmental Justice in Coastal NC

The history of environmental justice in North Carolina is multifaceted, shaped by pollution, racism, social justice, politics, human rights, law, and industrial practices.

A significant catalyst for the modern environmental justice movement in the State of North Carolina was the establishment of a hazardous waste landfill in a rural Black community in Warren County, which drew attention to the disproportionate environmental burdens borne by marginalized communities.

This event served as a stark example of the disproportionate environmental burdens marginalized communities face, triggering a wave of awareness and advocacy that continues today.

The history of environmental justice in coastal North Carolina is characterized by a complex interplay of environmental challenges, racial and socioeconomic disparities, and the activism and advocacy efforts of marginalized communities. This history can be divided into several key phases:

- Historical Disparities and Injustices (Pre-20th Century): Coastal North Carolina has a history of racial segregation and discrimination, with many communities of color located in vulnerable areas such as flood-prone coastal zones. These communities often had limited access to resources and opportunities, contributing to environmental disparities.

- Industrialization and Pollution (Mid-20th Century): The mid-20th century witnessed industrialization and the establishment of factories, power plants, and waste disposal sites in or near coastal communities. These facilities often had adverse environmental impacts, such as air and water pollution, which disproportionately affected low-income and minority communities.

- Hurricanes and Natural Disasters: Coastal North Carolina is prone to hurricanes and other natural disasters. Historically, the response and recovery efforts following these disasters have sometimes overlooked the needs of marginalized communities, leaving them more vulnerable to long-term environmental and economic harm.

- Environmental Movements and Activism (Late 20th Century): In the late 20th century, the environmental justice movement gained momentum. Grassroots organizations, such as the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, and local activists began to raise awareness about the unequal distribution of environmental burdens in coastal communities. These activists lobbied for policy changes and highlighted instances of environmental racism.

- Land Use and Zoning Policies: Historically, land use and zoning policies often favored industrial and commercial development in areas with lower land values, where low-income communities often resided. This led to the concentration of environmental hazards in these areas. Activists and policymakers have sought to reform these policies to promote more equitable land use planning.

- Environmental Legislation: In 1998, North Carolina became one of the first states in the United States to pass a state-level environmental justice policy, the Executive Order 80. This order directed state agencies to address environmental justice issues and promote equitable treatment of all communities.

- Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise (21st Century): Coastal North Carolina faces the challenges of climate change, including sea-level rise and increased frequency of extreme weather events. Low-income communities are often more vulnerable to the impacts of these changes and have limited resources for adaptation and mitigation.

- Environmental Justice Disasters: Several high-profile environmental disasters, such as the coal ash pond pollution case in the Dan River, have raised concerns about the impacts of pollution on communities. Additionally, Hurricane Florence in 2018 highlighted the need for more equitable disaster response and recovery efforts.Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in North Carolina have been a subject of significant concern when it comes to environmental justice. CAFOs are large-scale livestock operations where animals are raised in confinement, and they produce a substantial amount of waste. In North Carolina, the focus is primarily on swine and poultry CAFOs. The relationship between these facilities and environmental justice issues is multifaceted and involves several key aspects:

- Disproportionate Location in Marginalized Communities: CAFOs in North Carolina are often concentrated in low-income, rural, and predominantly minority communities, particularly in the eastern part of the state. This has led to a situation where marginalized communities bear a disproportionate burden of the environmental and health impacts associated with CAFOs.

- Air and Water Pollution: CAFOs produce vast quantities of animal waste, leading to the release of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other pollutants into the air. These emissions can result in poor air quality, which disproportionately affects the respiratory health of nearby residents. Moreover, improper waste management practices can lead to water pollution, impacting local waterways and threatening the availability of clean water for these communities.

- Health Impacts: Residents living near CAFOs often suffer from various health problems, including respiratory issues, nausea, and headaches, due to the exposure to noxious fumes and pollutants. Additionally, the contamination of local water sources can lead to waterborne illnesses. These health impacts are more severe in communities with limited access to healthcare resources.

- Quality of Life: CAFOs can negatively affect the overall quality of life in affected communities. Foul odors, flies, and noise pollution can disrupt daily life and reduce property values, leading to a decline in the socioeconomic well-being of the residents.

- Economic Disparities: Communities hosting CAFOs may initially see economic benefits, such as job creation, but these often do not compensate for the long-term environmental and health costs. Low-income residents who work in these operations may be particularly vulnerable to exploitation and inadequate labor protections.

- Regulatory Challenges: Regulatory oversight and enforcement related to CAFOs have been criticized for their lack of rigor and transparency, which can exacerbate environmental injustices. Weaker regulations and lax enforcement can allow CAFOs to operate with fewer safeguards for the environment and nearby communities.

- Community Activism and Legal Action: In response to these issues, grassroots organizations, environmental justice advocates, and affected communities have taken legal action and engaged in advocacy efforts to challenge the practices of CAFOs and demand stricter regulations and more protective policies. Their efforts aim to raise awareness about the environmental injustices associated with CAFOs and push for change.

- Governmental Reforms: Over the years, North Carolina has seen some reforms in response to environmental justice concerns related to CAFOs. Some changes have included moratoriums on new CAFO permits, more stringent regulations, and greater efforts to address issues like water quality and waste management.

CAFOs in North Carolina, particularly in marginalized communities, raises significant environmental justice concerns. Addressing these issues requires a combination of stronger regulatory measures, community engagement, legal action, and a commitment to equitable environmental protections that ensure the well-being and rights of all residents, regardless of their economic or racial background.

- Ongoing Advocacy and Solutions: Advocacy for environmental justice in coastal North Carolina continues to be a significant focus for community organizations, researchers, and policymakers. Efforts include improving access to clean water, affordable housing, and disaster resilience, as well as addressing pollution and climate change impacts.

The history of environmental justice in coastal North Carolina is marked by ongoing challenges and the resilience of communities affected by environmental disparities. There is still much work to be done to ensure that all residents of coastal NC have equal access to a safe and healthy environment. Join CCRW and other advocacy groups, committed to making long-lasting change.

SOURCES:

ADVOCACY:

Advocating for environmental justice in various pollution categories requires tailored strategies that are never one-size-fits-all.

Here’s how you can advocate for environmental justice from pollution sources in coastal NC:

Pollution from Industrialized Agriculture and Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)

- Education and Awareness: Advocate for transparency in agriculture practices and their environmental impacts. Educate communities about the consequences of industrialized agriculture and CAFOs, emphasizing how these practices disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

- Policy Advocacy: Push for stricter regulations on agricultural practices, including nutrient management and waste disposal. Support policies that address environmental and health concerns linked to agriculture pollution.

- Community Engagement: Partner with affected communities to raise their voices and concerns about agricultural pollution. Help communities access legal and support resources to hold agribusinesses accountable for their actions.

Loading...

Loading...

READ MORE INFO ABOUT CAFOS HERE.

Stormwater Pollution

- Community Action: Encourage local communities to participate actively in stormwater management, planning, and development processes, and make decision-makers aware of impacts on water quality and life in your community. Promote sustainable practices, such as installing rain gardens, permeable pavements, and other green infrastructure to reduce runoff pollution.

- Advocacy for Regulation: Advocate for stronger regulations and enforcement of stormwater management programs. Ensure that these regulations address the needs and concerns of all communities, not just wealthy neighborhoods.

- Education: Raise awareness about the importance of proper stormwater management and its impacts on all communities, emphasizing the need for equitable solutions.

- Citizen Science: Participate in the Adopt a Drain Program – click link here.

Industrial Pollution

- Support Regulation and Monitoring: Advocate for stricter industrial pollution regulations and demand regular emissions monitoring. Ensure that these regulations are consistently enforced and updated to protect vulnerable communities.

- Community Empowerment: Collaborate with impacted communities to help them understand their rights and legal avenues to hold polluting industries accountable for their actions. Support grassroots movements in their fight for environmental justice.

- Health Impact Assessment: Push for comprehensive health impact assessments in suspected contamination areas. Highlight the health disparities and make a call for action. Ask your local County Health Department to include the benefits of addressing Environmental Justice in Community Health assessments that are required to be updated by the State.

Plastic Pollution

- Plastic Reduction Initiatives: Advocate for policies and initiatives that reduce plastic consumption, such as bottle-bills, state-wide single-use bans, and promoting reusable and sustainable alternatives.

- Education and Outreach: Raise awareness about the environmental and health impacts of plastic pollution, particularly in disadvantaged communities. Encourage responsible plastic use and recycling. Join the NC Plastic Pollution Coalition.

- Lobby for Corporate Responsibility: Pressure corporations to take responsibility for their plastic waste and support plastic recycling and waste management programs, particularly in areas where vulnerable communities are disproportionately affected.

Pollution from Wastewater Treatment Practices

- Infrastructure Upgrades: Advocate for investments in wastewater treatment infrastructure to ensure it meets high environmental standards. This includes modernizing treatment facilities and improving sewer systems to prevent contamination.

- Community Access to Clean Water: Ensure that communities have access to clean and safe water, especially in areas affected by subpar wastewater treatment practices. Advocate for policies that address water affordability and equity.

- Government Oversight and Accountability: Push for stricter enforcement of wastewater treatment regulations and hold government agencies accountable for addressing wastewater-related pollution. Engage with regulatory bodies to advocate for better oversight.

For your area’s most current specific advocacy needs, please join our Advocacy Working Group.

It is essential to involve and empower affected communities, raise awareness, and support policies that promote equitable and just solutions to environmental pollution. Collaboration with environmental justice organizations, legal aid, and advocacy groups can enhance the effectiveness of these efforts. Please get in touch with Waterkeeper@coastalcarolinariverwatch.org if you would like to get involved in local advocacy efforts or join the CCRW Advocacy Working Group.

SOURCE:

(2021) Water Quality for Fisheries Assessment. Available at: https://coastalcarolinariverwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Industrial-Pollutants_WQ4F-Assessment-2021-1.pdf.

EVENTS/NEWS:

Shining the Light of Truth: The North Carolina Environmental Justice Summit

The 2023 North Carolina Environmental Justice Summit, held from October 20 to 21, was a powerful gathering of activists, scholars, and community leaders dedicated to addressing environmental injustices. This two-day event, organized by the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NC EJN), was a resounding call to expose false solutions and work collaboratively toward genuine repair.

The summit opened with an inspirational welcome from Rania Masri, Chris Hawn, and Elly Mendez Angulo Brown from the NC EJ Network. Naeema Muhammad, the creator and advisor of NC EJN, facilitated a thought-provoking session that encouraged participants to identify the false solutions in the Environmental Justice (EJ) movement, to understand the extent of environmental issues in their own backyards, and to recognize the often-overlooked allies in this fight for justice.

Naeema Muhammad articulated a powerful perspective, stating that “a false solution is that DEQ does not have the authority to protect communities.” She emphasized that everyone attending the summit was there due to the existence of these false solutions and that the primary focus should be on honest repair. The session tackled essential questions, such as why distressed communities are often made to bear the brunt of industrial pollution and why industries are not held responsible for the costs rather than passing them on to vulnerable communities.

Larry Baldwin, former Coastal Carolina Riverwatch Waterkeeper and Waterkeeper Alliance CAFO Director, added his perspective, highlighting that “a false solution is our General Assembly” and underlining the need for younger activists to step into leadership roles and even run for political office. The session proved to be an eye-opening experience, as it identified false solutions while celebrating the wins achieved by the EJ movement, instilling a renewed commitment to effecting change for all communities facing environmental injustices.

Throughout the afternoon, panel presentations showcased Environmental Justice victories. Donna Chavis discussed the win against the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Mac Legerton celebrated successes in battling toxic waste and landfills in Southeast North Carolina through the Robeson County Cooperative for Sustainable Development. Peter Gilbert emphasized the effectiveness of legal tools when working alongside communities, and Vivian Kennion shared the triumphant story of defeating Compute North. Ajamu Amiri Dillahunt moderated the presentations, reinforcing that organized efforts can yield victories.

On the evening of the same day, EJ research presentations delved into the scientific aspects of environmental justice. Akirah Epps evaluated satellite ammonia observations for understanding air pollution inequalities related to Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). Liz Shapiro-Garza focused on increasing access to information and policy-making for communities impacted by chemical contaminants in wild-caught fish. Andrew George addressed drinking water contamination and health injustices facing private well users in North Carolina, a point also made by Jeff Currie, the Lumber Riverkeeper, about financial disparities and how “being poor takes a lot of money.” Joe Bowman highlighted the benefits of incorporating environmental justice community-engaged research in county-required Community Health Assessments.

The first day concluded with an awards ceremony and a fireside chat, where participants reflected on the day’s events and recognized the achievements of those committed to environmental justice.

On the second day of the summit, they commenced with a deep dive into the challenges of doing grassroots work within an oppressive state and capitalist system. Adrienne Kennedy and Shalonda Regan, representing the Seeds of H.O.P.E. Project and Disaster Recovery Relief Center, shared their experiences. Shalonda Regan’s words, “You have to put yourself in a wave of humanity. If they divide us, they will conquer,” echoed the spirit of unity and resilience that permeated the summit.

Workshops throughout the day covered critical topics, including the threat of manure biogas and other dangers associated with the growth of industrial agriculture and Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). Donna Chavis, Mac Legerton, Jeff Currie, and Sherri White-Williamson shared their expertise, emphasizing the urgency of addressing these issues.

Another workshop explored the consequences of Duke Energy’s Climate and Community-Wrecking Grid Scheme, led by NC Warn’s Falicia Wang and Sara Heilman, who discussed environmental and community impacts.

The summit also featured other meetings that touched on topics such as toxic waste sites, pollution, and justice and discussions surrounding democracy, redistricting, and representation. These sessions, led by dedicated individuals and organizations, provided valuable insights into the multifaceted aspects of the environmental justice movement.

The 2023 North Carolina Environmental Justice Summit left a lasting impact on attendees, including CCRW Executive Director Lisa Rider and Board Director President Katie Tomberlin, illuminating the path forward for those committed to eradicating environmental injustices.

The event served as a testament to the power of collective action, truth-telling, and honest repair in the ongoing struggle for environmental justice. The summit demonstrated that change is possible when communities, activists, scholars, lawyers, and allies come together to address these critical issues.

SOURCE:

‘NC Environmental Justice Summit 2023: False Solutions, Honest Repair’ (October 20-21, 2023) Franklin Center, Whitakers, NC.

SOURCE: NC DEQ

Fish Advisories in Coastal NC: An Environmental Injustice Caused by Industry

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) is recommending limitations on the consumption of specific freshwater fish from the middle and lower Cape Fear River, due to concerns about exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) found in fish samples from that region. PFOS is a member of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) group, often dubbed “forever chemicals” because of their persistence in the environment. These recommendations stem from new data and insights from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Many states issue comparable guidelines to restrict or advise against consuming certain fish, considering the differential impacts on marginalized communities.

Fish advisories are a critical tool to balance the nutritional value of fish with the potential risks associated with pollutants accumulated from the surrounding environment. Fish constitute a significant source of sustenance and nutrition for many North Carolinians, offering essential proteins, healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals. This is particularly vital for underserved communities. Environmental justice considerations come into play as these communities often bear the brunt of pollution and may rely more heavily on fish as a dietary staple.

PFAS, as an emerging public health concern, raise concerns about environmental justice, as various sources of exposure, including contaminated drinking water, food, indoor dust, consumer products, and workplaces, disproportionately affect marginalized communities. Exposure to PFAS through fish may be even higher among these communities, as they might rely more on subsistence fishing. Research has indicated various health issues linked to PFAS, with prolonged exposure particularly worrisome. These effects include adverse impacts on child growth, learning, and behavior, reduced fertility, thyroid dysfunction, elevated cholesterol levels, weakened immune responses, and a higher risk of certain cancers. Vulnerable communities are often the most affected, exacerbating environmental justice disparities.

Subsistence fisheries, vital for many marginalized communities’ livelihoods and cultural identity, face significant risks. The recommendations specify limits for certain species and particular demographic groups, with even stricter limits for women of childbearing age, pregnant women, nursing mothers, and children, acknowledging their heightened sensitivity to PFAS exposure. Children, women under 44, and pregnant or breastfeeding individuals are advised to abstain from consuming several fish species from the Middle and Lower Cape Fear River, with a maximum recommended one to seven meals per year for everyone.

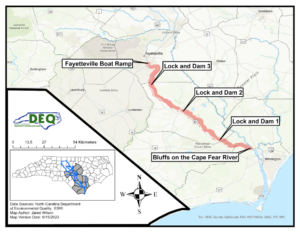

The advisory pertains to several species of catfish, bass, bluegill, redder, and American Shad, all found to contain toxic PFOS, a type of PFAS. The environmental justice dimension emerges as these marginalized communities often rely on these species for sustenance. The affected region of the Cape Fear River starts at the Fayetteville boat ramp and extends southeast to the Bluffs, just north of Wilmington. These communities are at the forefront of the environmental justice issue as they face compounded health and economic challenges.

PFAS compounds are pervasive in the environment and are present in numerous consumer products, including those used by marginalized communities. In the Lower Cape Fear, Chemours is a significant source of these compounds, including PFOS, through its Fayetteville Works Plant. This facility discharged PFOS, GenX, and other PFAS into the Cape Fear River, underscoring the environmental justice dilemma, as these communities often shoulder the burdens of industrial pollution.

This advisory holds particular significance for subsistence fishing communities, as they often depend on fishing for sustenance. A Duke University study revealed that people fishing in the Lower Cape Fear region frequently favor catfish and bass. Moreover, they often share their catches widely with family and friends, highlighting the interdependence of these marginalized communities.

Duke University researchers underscore the environmental justice aspect, concluding that people in the Lower Cape Fear River region continue to consume fish, sometimes out of necessity, despite potential health risks as per current state advisories. These researchers advocate for increased resources and innovative strategies to reach marginalized populations, communicate risks effectively, and provide alternatives for wild-caught fish consumers. They also emphasize the limitations in North Carolina’s fish consumption advisory process, particularly in assessing the full health risks for subsistence fish consumers, thus accentuating the environmental justice disparities.

To address environmental justice concerns related to PFAS exposure, individuals can use the NCDHHS Clinician Memo to discuss potential health effects with their healthcare providers. Reducing PFAS exposure is challenging as it permeates many food products and the environment. Environmental justice communities often lack alternatives and resources to mitigate these risks, exacerbating the need for environmental justice advocacy.

NCDHHS collaborates with local health departments and community-based organizations to disseminate information about PFAS in fish, mainly focusing on underserved communities. This information is available on the NCDHHS fish consumption advisories webpage.

Communities in the Middle and Lower Cape Fear Region, often composed of marginalized populations, have been seeking information about PFAS in fish since the discovery of GenX in the river. Dr. Zack Moore, DHHS state epidemiologist, acknowledged the issue’s complexity and expressed hope that the information provided would empower underserved residents to make informed decisions for themselves and their families. Addressing the environmental justice aspects of this problem is a crucial step toward a more equitable and sustainable future.

Coastal Carolina Riverwatch urges industry and political leaders to prioritize environmental justice and take action to address pollution at its source. CCRW is working with Dr. Lee Ferguson, Duke University, to study PFAS and heavy metal contamination in the White Oak River Basin in the coming years.

SOURCE:

Lisa Sorg, N.N.J. 13 (2023) Because of pfas contamination, eat very little, if any fish from the middle and lower cape fear river, state health officials advise, NC Newsline. Available at: https://ncnewsline.com/briefs/because-of-pfas-contamination-eat-very-little-if-any-fish-from-the-middle-and-lower-cape-fear-river-state-health-officials-advise/.

NCDHHS recommends limiting fish consumption from the middle and lower cape fear river due to contamination with ‘Forever chemicals’ (2023) NCDHHS. Available at: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2023/07/13/ncdhhs-recommends-limiting-fish-consumption-middle-and-lower-cape-fear-river-due-contamination.

NC Environmental Justice for Indigenous People

Environmental justice for Indigenous people in North Carolina encompasses a range of interconnected concerns rooted in land rights, health, culture, and social justice.

Indigenous communities, like the Lumbee, Coharie, and Haliwa-Saponi, emphasize the importance of land rights and sovereignty, focusing on protecting ancestral territories, addressing land tenure, and safeguarding culturally significant sites.

Moreover, environmental impact assessments are crucial to ensure development projects do not harm Indigenous lands, especially considering the potential for disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards.

Clean and safe water access, reducing health disparities linked to environmental factors, and preserving cultural practices also feature prominently in their pursuit of environmental justice.

“Environmental Justice and the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina: An Analysis of the Proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline” by Bryant (2014), explores the environmental justice implications of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline on the Lumbee Tribe.

Environmental justice concerns raised by the Lumbee Tribe center around the pipeline’s impact on their ancestral lands, cultural heritage, and water resources. Bryant underscores the significance of engaging in meaningful consultation and obtaining consent from Indigenous communities in decision-making processes. He stresses the necessity of comprehensive environmental impact assessments to protect Indigenous lands.

“Environmental Justice and the Coharie Tribe of North Carolina: A Case Study of Industrial Pollution” by McRae (2019), offers a case study that focuses on the environmental justice challenges faced by the Coharie Tribe concerning industrial pollution. It scrutinizes the disproportionate exposure of the tribe to environmental hazards and the resulting health disparities. The study underscores the importance of providing clean and safe water access and advocates for regulatory measures to address the ecological impacts on Indigenous communities. This is a real-world example of environmental justice concerns, highlighting the health and ecological disparities faced by the Coharie Tribe due to industrial pollution.

Meaningful consultation, consent, and legal protections are fundamental in decision-making and enforcing rights. Addressing climate change resilience and supporting sustainable economic development opportunities that align with Indigenous values are integral to the movement.

In collaboration with various stakeholders, Indigenous communities aim to rectify historical injustices, protect their lands and resources, and promote community well-being while respecting their cultural heritage and self-determination.

SOURCES:

Bryant, B. (2014). Environmental justice and the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina: An analysis of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Environmental Justice, 7(6), 191-196.

McRae, L. (2019). Environmental justice and the Coharie Tribe of North Carolina: A case study of industrial pollution. Environmental Justice, 12(1), 1-7.

Eastern North Carolina Communities Oppose Crypto-mining Operations Near School

Cryptocurrency mining has become a topic of discussion and controversy in Greenville, particularly in relation to the Compute North project. The Greenville Utilities board held closed-door meetings throughout 2021 to discuss economic development issues, including a $50,000 incentive for the cryptocurrency mining operation.

The discussions followed appropriate procedures, but a board member, Ferrell Blount, recused himself due to a conflict of interest. Compute North initially planned to build a data processing site in Pitt County, but faced opposition when applying for a special-use permit near Belvoir Elementary School.

The Greenville City Council later approved a zoning amendment allowing companies like Compute North to operate in the city. There were rumors of a potential facility location on property owned by board member Ferrell Blount, but Compute North eventually halted its project due to economic uncertainties and filed for bankruptcy. The community expressed concerns about the Compute North project, particularly regarding energy consumption and noise generated by cooling systems.

These concerns led to opposition and calls for a moratorium on cryptocurrency mining facilities. The impact of cryptocurrency mining on the environment and local communities has raised significant environmental justice concerns. Mining operations require a substantial amount of electricity, straining local power resources and contributing to increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Local communities near mining operations often experience disruptions to their daily lives, including increased noise, traffic, and environmental pollution. Additionally, mining operations can strain local resources, such as water, which may already be in short supply in certain areas.

Addressing these environmental justice concerns requires a comprehensive approach. Governments can play a pivotal role by implementing regulations to reduce the carbon footprint of cryptocurrency mining and ensuring adherence to environmental standards . Transparency from mining operations regarding their energy sources and practices is essential.

Community involvement should be encouraged to give affected communities a voice in the process and mitigate negative impacts. Promoting the use of renewable energy sources for mining operations can help alleviate environmental issues.

The discussions and controversies surrounding the Compute North project in Greenville highlight the environmental and social concerns associated with cryptocurrency mining. It is crucial for governments, mining operations, and communities to work together to address these concerns and find a balance between the potential benefits of blockchain technology and the protection of the environment and local communities.

Call Lisa Tyson with NOTRA (252) 327-1818 for more info on this advocacy effort.

SOURCES:

Writer, G.L. (2022) GUC leader, board minutes reveal dealings with crypto miner, Reflector. Available at: https://www.reflector.com/news/local/guc-leader-board-minutes-reveal-dealings-with-crypto-miner/article_6d2da301-fcfe-59b4-8a0c-79013a15dbc7.html.

Fairley, P. (2017). Bitcoin’s insane energy consumption, explained. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/renewables/bitcoins-insane-energy-consumption-explained

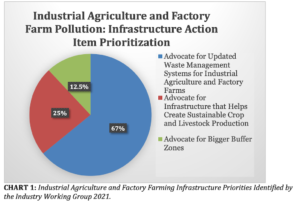

de Vries, A. (2018). Bitcoin’s growing energy problem. Joule, 2(5), 801-805. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.04.016 3. Stoll, C., Kizys, R., & Pierdzioch, C. (2019). The environmental impact of cryptocurrencies: A systematic review. Joule, 3(7), 1647-1661. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.05.012 4. Mnif, M., Alqahtani, F., & Alqahtani, A. (2021). Environmental impact of cryptocurrencies: A systematic review. Sustainable Business Review, 3(1), 1-16. doi:10.1108/SBR-02-2021-0016