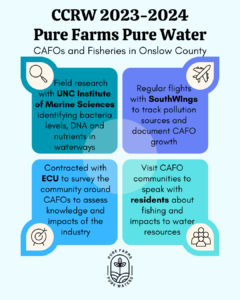

Through the Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign with Waterkeeper Alliance, Coastal Carolina Riverwatch works with other NC Waterkeepers and several amazing statewide advocates to address the impacts of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) on local waterways.

The Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign calls attention to the destructive pollution practices of industrial agriculture and factory farms, advocates compliance with environmental laws, and supports the traditional family farms that industrial practices endanger. The Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign addresses the failure to regulate pollution from industrialized swine, poultry, and dairy facilities that are devastating rivers, lakes, and estuaries and lowering the quality of life in our communities.

Coastal Carolina Riverwatch (CCRW) educates the public about the impacts on the quality of water and quality of life, supports communities and local farmers, and advocates for sustainable food systems.

We work to help decision-makers understand the need to strengthen and enforce existing rules on the discharge of animal waste into our waterways, seek to hold corporations that dictate facility operations accountable for waste management practices, promote best management policies that protect our waterways, and support independent farmers, and take legal action against violators.

“CAFO pollution has affected North Carolinians for decades. Each year, NC hogs produce 10 billion gallons of manure. This unmanageable amount of waste is contaminating our waterways and harming our communities. In our watershed, the New River is most heavily impacted. Coastal Carolina Riverwatch collects regular water samples surrounding these facilities to analyze for fecal bacteria. We also conduct watershed flyovers to look for pollution violations. By collecting this data, we can work with several statewide partners to advocate for the reform of these destructive industries”. -Rebecca Drohan, former Waterkeeper, Coastal Carolina Riverwatch (in photo).

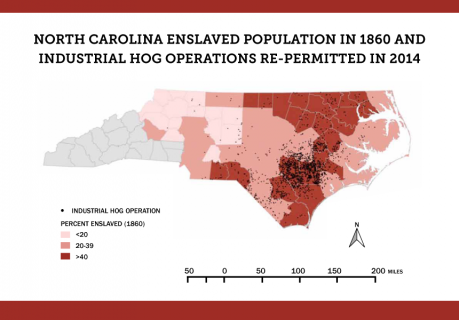

“This is not only a water quality problem, but also a justice problem. Communities that surround these densely packed farms are disproportionately affected by noxious odors, loud industrial noises, and the threat of hog waste flowing into their homes during storms. These communities are much more likely to be communities of color and low income, which makes this an environmental justice issue.” – Riley Lewis, White Oak Waterkeeper

Click to learn more about the completion of this research.

North Carolina’s hogs produce 10 billion gallons of manure each year. Hog waste is stored in large open-air “lagoons”, or cesspools. Liquid from these pools is sprayed onto adjacent fields for disposal. As the waste is sprayed, it can run into our waterways. During heavy rain events, lagoons can fail. Millions of gallons of untreated waste can be spilled and animals are left to die.

Though safe waste management of swine operations is severely lacking, these facilities are subject to State permitting and regulations. Poultry operations are not. NC’s poultry industry is rapidly growing with very little oversight and almost no public records.

NC poultry operations produce 5 million tons of waste per year. Poultry waste, mixed with bedding and carcasses is stored in large piles. These piles are often left uncovered, easily blown away by wind, or washed into our waters. Due to a lack of transparency within the industry, very little is known about where this waste is transported and how it is disposed.

Swine and poultry pollution have severe impacts on the environment and on public health.

CAFO waste contains:

- Urine and feces

- E. coli and other pathogens

- Nitrogen, phosphorus, and ammonia

- Antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Pharmaceuticals

- Hormones

- Heavy metals

When CAFO waste enters the environment, these contaminants come with it. This can pollute soil and groundwater, and make surface waters unsafe to recreate in. Nutrient overload from nitrogen and phosphorus can cause harmful algae blooms and fish kills. Many of these operations were built in areas prone to flooding. During heavy rain events, massive amounts of waste can be spilled and animals are left to die. CAFO waste can also enter the air as particulate matter.

Communities surrounding these facilities are impacted with diminished quality of life due to overwhelming odors and health complications from air and water pollution. These impacts disproportionately affect communities of low income and/or People of Color, making CAFOs a significant environmental justice issue.

In the past CCRW has worked with the residents of the White Oak River Basin and other environmental nonprofits to influence CAFO regulations.

In 2023, the North Carolina Swine, Poultry, Cattle and Biogas General Permits were up for review. North Carolinians had a chance to tell the NC Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to update four general permits for the state’s industrial animal operations so that they would better protect our health, rivers, and drinking water. CCRW believed that DEQ must also address the cumulative and racially discriminatory impacts borne by communities where these operations are concentrated. DEQ conducted a “stakeholder” process including a public meetings and the opportunity to submit comments by phone, email, or mail.

The Background:

- Most of the state’s 2,200 industrial hog operations rely on a primitive system to manage hog waste that involves storing untreated urine and feces in unlined pits and spraying the waste on nearby fields. This system, called the lagoon and sprayfield system, causes devastating water and air pollution; nearby families get sick and die at higher rates than people living farther away. These operations disproportionately cause harm to Black, Latino, Native American, and low-wealth rural communities.

- The state’s swine “general permit” regulates how animal operations manage billions of gallons of animal waste at industrial animal operations; the general permit allows these operations to use the lagoon and sprayfield system.

- The state’s digester “general permit” regulates how animal waste is handled at industrial hog operations that propose to cover some of their hog waste pits to capture certain gasses and make energy, which is often called “biogas,” while leaving the rest of the harmful system in place and even increasing some harmful impacts.

- DEQ is in charge of these permits, and it is soliciting stakeholder input before renewing them in 2024 for five more years.

| CCRW’s contributions:

During this DEQ permit process, the White Oak Waterkeeper attended the industry stakeholder drafting meeting hosted by DEQ, shared written, recorded and in-person comments in favor of water quality, hosted a stop for Waterkeeper Alliance’s comments tour, and hosted a screening of The Smell of Money for students in the WORB. Through these processes, CCRW and community advocates contributed over 30 written comments, emphasizing the need for stronger surface water protections. |

Photo: LEWIS. Attendees of the student Smell of Money screening at Carteret Community College. |

PARTNERS:

![]()